Executive Summary

The data management market is in the midst of revolutionary change. One need only glance at the business and technology press for evidence. Oracle, the dominant player in the relational database market, is missing new database license revenue targets quarter after quarter. Meanwhile, Teradata, a company synonymous with the enterprise data warehouse, has lost over $6 billion in market capitalization over the last two-plus years as its largest customers reduce their spend with the company. And SAP, the stalwart ERP and business intelligence vendor, is working hard to position HANA as the be-all-end-all in database technology … with limited success.

These struggles are the result of enterprise practitioners, both on the IT and business sides of the house, who are frustrated with the data management status quo. These frustrations include:

1. Cost. Data volumes are growing exponentially year-after-year while IT budgets remain flat. Simple mathematics dictates that the current data management paradigm is simply unsustainable from an economic standpoint. Enterprises are forced to devote more and more of their stagnant IT budgets to scale existing, traditional data management systems, leaving fewer funds to support innovation and value-add projects.

2. Performance. Traditional data management technologies are buckling under the weight of Big Data. Conversations with members of the Wikibon community make clear that as both data volumes and the complexity of analytic workloads increase, relational database management systems and related data management tools are unable to provide the level of performance required to meet demanding business conditions.

3. Agility. In addition to performance, traditional data management approaches require lengthy data preparation and data modeling work, making it virtually impossible for practitioners to adapt both analytical workloads and transactional applications at the pace required to keep up with end-use (workers, partners, customers, etc.) expectations.

In years past, practitioners had little option but to stick with these traditional approaches to data management as there were few if any accessible alternatives on the market. But times have changed.

Today, practitioners have a plethora of alternatives to choose from. The two most prominent of these have emerged from practitioners themselves (specifically practitioners are Web companies such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook) and the open source communities that have developed around them. The first is Hadoop – the open source Big Data framework for storing, processing and analyzing massive volumes of multi-structured data – which has emerged as the de facto foundational technology in the modern data management stack. The second is NoSQL, a style of database that eschews relational structure for a more flexible approach that enables developers to build interactive, scalable data-centric applications incorporating data of virtually any type.

As Hadoop and the various flavors of NoSQL have matured so have the commercial entities that are developing products and services around them and the enterprise practitioners that are deploying them.

Nearly a full third of enterprise Big Data practitioners, for example, have deployed Hadoop in production environments, according to Wikibon’s recent Big Data Analytics Adoption Survey. Practitioners are also keen on leveraging the cloud to support Big Data workloads, with more than 50% using cloud-based Big Data tools and technologies as part of existing projects.

But it is still early days for Big Data in the enterprise. Over 40% of Big Data early adopters are still in the evaluation phase and close to 30% still experimenting with pilot projects. This reality is reflected in the current size of the Big Data market and its forecasted growth rate over the next four years.

Specifically, total revenue generated by sale of Hadoop distribution software/support subscriptions and related professional services in 2014 is $621 million. The market is expected to nearly triple in size by 2017, however, reaching close to $1.7 billion as many pilot projects blossom into full-blown production deployments.

As for the NoSQL market, total revenue for related software , subscription support and professional services reached $461 million in 2014 and is forecast to grow at even faster clip than the Hadoop market reaching over $1.6 billion in 2017. This growth is being driven in large part by demanding end-users that expect the same level of functionality and simplicity they get from consumer applications such as Google search.

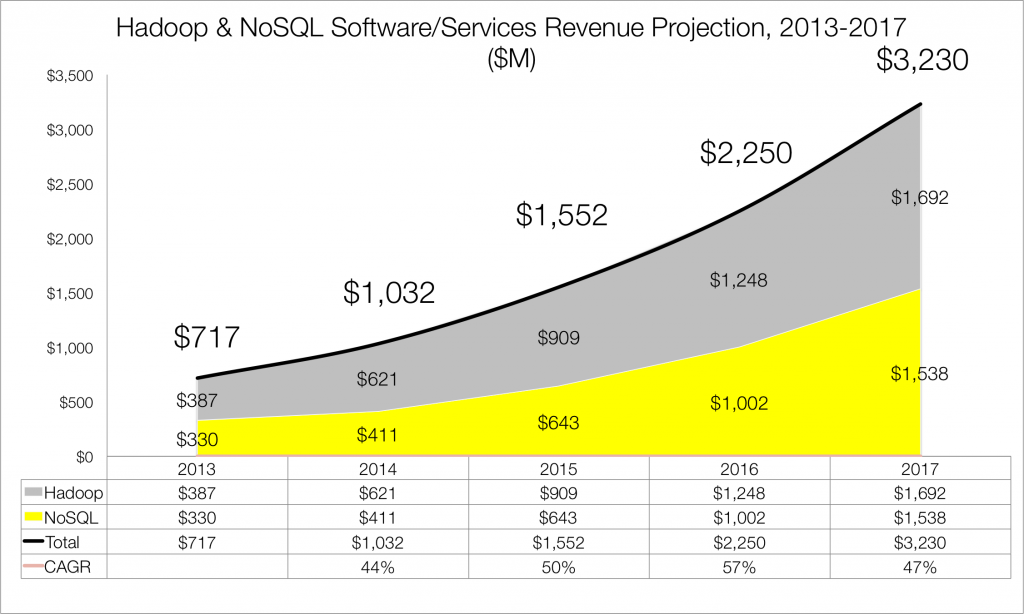

Combined, the Hadoop and NoSQL markets will reach over $3.3 billion in 2017 representing a 46% CAGR over the four year period (See Figure 1).

What follows in the remainder of this report is more detailed analysis of both the Hadoop and NoSQL markets, including revenue breakdown by vendor, analysis of market drivers and market headwinds, a review of the major developments in each market over the last twelve months and their relative impact on market growth, and expectations for market developments in 2015 and beyond.

Hadoop Market Forecast

The market for Hadoop distribution software, support subscriptions, cloud services and related professional services topped $620 million in 2014 as measured by vendor revenue. This is up from $387 million 2013, a year-over-year growth rate of 60%. Over the next four years, Wikibon forecasts this market to grow to nearly $1.7 billion, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 40%.

This forecast does not include related hardware revenue nor complimentary Hadoop-based tools such as data visualization, data transformation and data integration software.

The current Hadoop market is significantly fragmented, with seven vendors generating 64% of total revenue. Comparing these seven vendors is made difficult due to their varying business models and product/services on offer. One vendor (Accenture), for example, derives all of its Hadoop-based revenue through professional services, while another (Amazon) does so exclusively through cloud-based software. Yet another (Hortonworks) offers a Hadoop distribution, but does not charge license or subscription fees for its use, but generates revenue through a support subscription offering along with professional services. With those caveats made clear, below is a vendor-by-vendor revenue breakdown of the top seven Hadoop vendors for the calendar year 2014 (See Figure 2).

Looking at market share, Cloudera, one of three Hadoop pure-play vendors, leads the pack at 13%. IBM, whose Hadoop revenue is largely driven by its Global Business Services unit, and Accenture both captured approximately 10% market share. Amazon Web Service followed close behind at 9% market share thanks to its cloud-based ELastic MapReduce offering. MapR and Hortonworks, the other two Hadoop pure-plays, both checked in with 7% share followed by Pivotal, the EMC-VMware spinoff, with 6%. The remaining 36% of the market is divided amongst various professional services firms, independent software vendors (ISVs) and value-added resellers (VARs).

Hadoop Market Drivers

The Hadoop market in 2014 is being driven by two main factors. The first is the increasing costs associated with processing and storing ever growing data volumes. Enterprises across verticals are being inundated with data from all directions, from both inside and outside corporate data centers. In addition to growth of traditional data sources, new sources of data associated with the Internet of Things and the Industrial Internet are leading to now incremental but exponential overall data growth in many industries.

Processing and storing ever-increasing data volumes with traditional enterprise data warehouses and related data integration technology, and their legacy pricing models, is taxing stagnant IT budgets. Data management professionals are forced to allocate more and more of their budgets to expanding expensive software licenses and maintenance contracts, a pricing model that was sustainable if not ideal when data growth was more modest. In the current environment, enterprise practitioners are increasingly coming to the conclusion that a new approach is needed.

For many, that new approach involves Hadoop. Based on direct feedback from data management practitioners and the Wikibon community, it is clear that a small but growing percentage of enterprises are baselining their current spend on traditional data warehouse and related technology by moving data and workloads to Hadoop. More to the point, these practitioners are keeping only the most current, or “hot”, data in traditional EDWs and moving older data to Hadoop. Specifically, according to Wikibon’s 2014 Big Data adoption survey, fully 61% of practitioners that have deployed Hadoop have shifted one or more workloads from a legacy data warehouse or mainframe to the open source Big Data platform. The most popular workload being shifted to Hadoop is large-scale data transformations, but business intelligence and reporting workloads are not far behind.

Hadoop costs are just a fraction of traditional commercial data warehouse technology as it is based on open source hardware that runs on scale-out commodity hardware, resulting in significant costs savings for budget-taxed IT departments.

The second Hadoop driver is the realization by many enterprises that in order to remain competitive in the current economic and business climate they must leverage all the data at their disposal to make smarter data-driven decisions. This is simply not possible with traditional data warehouse technology, which is designed to support structured, relational data. The majority of net-new data, however, is semi-structured and unstructured. This includes machine-generated data from mobile devices and industrial equipment, sensor data associated with the Internet of Things, and text-based data such as the content of social media posts, emails, and documents.

Hadoop, and the underlying Hadoop Distributed File System, is an environment ideal for storing and processing semi-structured and unstructured data. There are also a number of related technologies and tooling at various stages of development to make it easier for developers to build applications that enable business users – not just advanced Data Scientists – to interact with Hadoop-based data in various ways. These include YARN, which enables developers to interact with Hadoop data in myriad new ways beyond MapReduce (including the increasingly popular in-memory Spark framework), and SQL-like databases such as Cloudera’s Impala and the latest iteration of Hive (spearheaded by Hortonworks) that provide a hook into business intelligence tools for non-expert end-users.

The first driver – cost savings – is largely IT-led, while the second driver – the ability to analyze all data for better decision-making – is largely business led.

Hadoop Market Headwinds

While Hadoop holds much promise, there are a number of barriers holding back the market in 2014.

The first, and most obvious, is that Hadoop itself is still relatively immature. This despite the immense progress made by both commercial Hadoop vendors and the open source community in improving the usability of Hadoop and beefing up its enterprise-grade features in the areas of security, high availability, and backup and recovery. Before practitioners are willing to use Hadoop to support production-grade applications in which SLAs must be met, they need assurance that it meets the minimum level requirements in these areas. In Wikibon’s 2014 adoption survey, concerns around enterprise-grade features were identified as the major roadblocks to expanding deployments to full-scale production. This is important to the market’s growth from a vendor-revenue perspective because the majority of Hadoop software and subscription offerings are geared towards supporting production deployments.

A related barrier to adoption is the lack of skilled Hadoop practitioners. This includes not just Data Scientists, who are tasked with building predictive models and algorithms, but developers, engineers and operations pros that are tasked with standing up Hadoop deployments and administering them as use cases and users grow over time. As Hadoop becomes easier to deploy and manage, this barrier will recede as less expertise will be required to support deployments.

The flipside, of course, is that Hadoop professional services are in high demand precisely because the open source Big Data framework is complex. Early Hadoop adopters across verticals are increasingly turning to professional services firms, both large multi-national consulting firms and small boutique shops, to aid them in fleshing out use cases, architecting systems, deploying the technology and building applications. Over 60% of Hadoop revenue in 2014 was from professional services, with less than 40% for Hadoop software and support subscriptions. It is not surprising, then, that IBM and Accenture round out the top three Hadoop vendors by revenue.

Amazon Web Services, meanwhile, quitely grew its Hadoop business significantly in 2014 as more and more early adopters looked to the public cloud to begin experimenting with Big Data application development and related analytics. According to Wikibon’s 2014 Big Data adoption survey, fully 58% of practitioners are leveraging the public cloud for at least some part of existing Big Data projects. As with all AWS offerings, Elastic MapReduce significantly lowers the barriers to adoption for Hadoop by eliminating the need on the part of practitioners to procure, deploy and tune hardware. Whether these Hadoop practitioners will continue leveraging AWS when deployments move to production status is an open question.

Major Hadoop Market Developments

The biggest supply-side question on the minds of vendors and investors today is some variation of: Is it possible to make money in the Hadoop market? More specifically, can anyone build a large and successful Hadoop software (not professional services) company? Wikibon believes the answer is yes, but it is far from a sure thing and clearly not going to be easy.

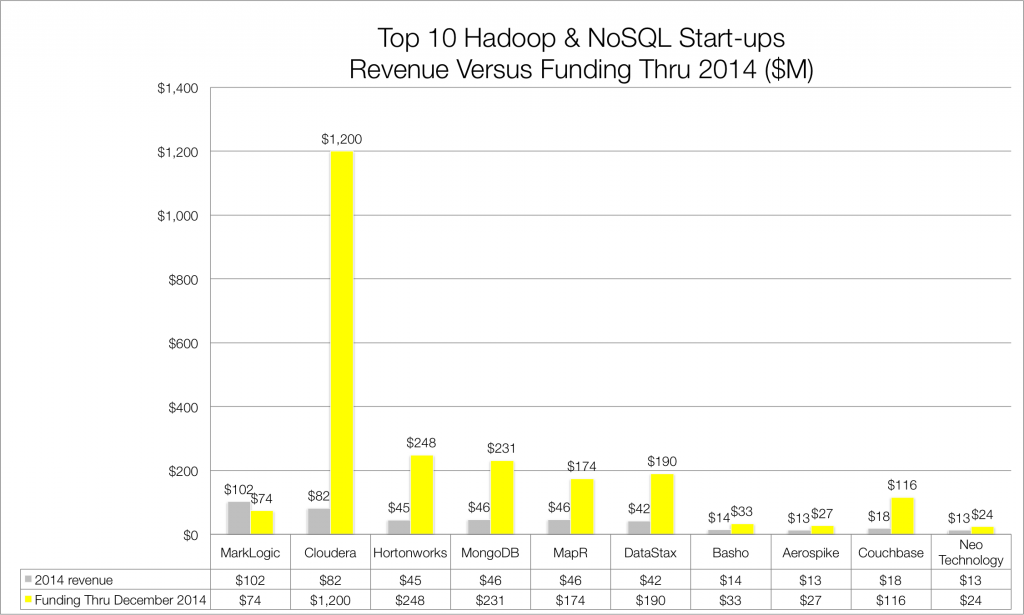

The market got a first-hand look at just how difficult it is to build a Hadoop business in November 2014 when Hortonworks filed an S-1. The company, which was spun out of Yahoo in 2011, reported revenue figures that largely underwhelmed market expectations. Specifically, for the twelve months ending April 30, 2013, Hortonworks generated just under $11 million in revenue. For the nine months ended September 30, 2014, it generated $33 million in revenue. For full year 2014, Wikibon estimates Hortonworks revenue to come in at $45 million.

While lower than many previous estimates, Hortonworks’ overall revenue figures are solid when considering the company is just three and a half years old, that it has only had a product on the market since 2012 and that it is executing a business model unique in the industry. That is, Hortonworks’ Hadoop distribution, called Hortonworks Data Platform, is made up entirely of open source components and is free for anyone to download and use. The company makes money through a three-level maintenance and support subscription as well as professional services, though Hortonworks executives have clearly stated they intend the latter to make up only a small fraction of their business in the long term.

This is an important point because building a large, profitable Hadoop professional services company from scratch would be an extremely difficult undertaking. So what is more concerning about the Hortonworks S1 than overall revenue is the percentage of revenue coming from professional services and the negative margin associated with this revenue. For the nine months ended September 30, 2014, 43% of revenue was from professional services with a -35% operating margin. During that time the company generated $14.2 million in revenue from professional services at a cost of $19.1 million resulting in a net loss of nearly $5 million.

These numbers highlight just how expensive it is to provide professional support services for complex Hadoop deployments and reinforce the notion that Hortonworks must transition more of its revenue to repeatable software and maintenance support subscriptions. The problem for Hortonworks, indeed for all Hadoop pure-play vendors, is that through 2014 only a fraction of Hadoop practitioners are paying for the software. According to findings from Wikibon’s 2014 Big Data adoption survey, just 25% of Hadoop practitioners are paying customers of one of the commercial Hadoop distribution vendors. 75% are using Hadoop software without paying a nickel to do so.

Clearly the Hadoop market is still in its early days, but Wikibon remains bullish on the long-term prospects of Hadoop vendors generally and Hortonworks specifically. Hortonworks’ strategy has always been to position itself to capitalize when Hadoop crosses the chasm from early adopters to mainstream adopters. Hortonworks is still positioned to do that and Wikibon expects revenue to ramp up considerably over the coming twelve to eighteen months as production deployments expand in the financial services, retail and telecommunication sectors.

Another notable event of 2014 was the massive investment by Intel in Cloudera (See Figure 3). Specifically, Intel invested $740 million for an 18% equity stake in Cloudera, the first Hadoop distribution vendor to market in 2009. The investment pushed total capital raised by the Palo Alto company over the $1 billion mark, an outrageous sum even in the current venture capital climate. As part of the investment, Intel announced it was abandoning its own Hadoop distribution and integrating its IP, which focused largely on chip-level security for Hadoop, into Cloudera’s platform. Cloudera also took over Intel’s Hadoop clients, most in Asia, and gained the benefit of Intel as a strategic reseller.

The Intel-Cloudera deal wasn’t the only notable venture capital news of 2014. In June, Google Capital announced a $110 million in MapR, bringing total capital raised by MapR to $174 million. In July, HP announced a $50 million equity investment in Hortonworks for a 5% stake in the company, bringing total capital raised by Hortonworks to nearly $250 million. This leaves all three Hadoop pure-play vendors well capitalized heading into 2015.

Hadoop Market in 2015 and Beyond

Wikibon believes the market for Hadoop software and support subscriptions is poised for significant growth over the next one to five years. As early adopters transition Hadoop from PoC to production deployments and eventually to full-scale platform status, they will increasingly turn to commercial vendors for help troubleshooting, managing, scaling and securing these platforms. Indeed, Hortonworks’ maintenance and support subscription, as well as Cloudera’s enterprise data hub offering and MapR’s various platform offerings are aimed at production-grade deployments.

Wikibon forecasts the Hadoop market for software and support subscriptions as well as professional services to grow to $909 million in 2015 from $621 million in 2014. That represents year-over-year growth of 46% at a time when enterprise software overall is growing at low single digits. Looking ahead, the Hadoop market will cross the $1 billion mark in 2016 reaching nearly $1.25 billion, then topping $1.6 billion in 2017.

NoSQL Market Forecast

The market for NoSQL database software, support subscriptions, cloud services and related professional services reached $411 million in 2014 as measured by vendor revenue. This is up from $330 million 2013, a year-over-year growth rate of 25%. Over the next four years, Wikibon forecasts this market to grow to over $1.5 billion, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 55%.

This forecast does not include related hardware revenue nor complimentary NoSQL-related tools such as data integration software.

The current NoSQ market is highly fragmented. As stated in the Executive Summary of this report, there are numerous flavors of NoSQL database, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. These NoSQL databases include key-value stores, document databases, column stores and graph databases. Most of these databases started life inside practitioner organizations, such as Facebook and even the National Security Agency, where they were developed to solve specific problems that traditional relational databases technology could not.

The result is that no one NoSQL database has emerged as a general purpose database to support most use cases, hence the fragmented nature of the market. This is in contrast to Hadoop, which has emerged as the de facto Big Data storage and processing platform for both start-ups and enterprises.

A number of start-ups have emerged that are commercializing the various NoSQL databases on the market. In most cases, a single vendor has come to dominate the particular NoSQL database in question. For example, DataStax is the dominant vendor commercializing Apache Cassandra, a NoSQL column store database originally developed at Facebook. MongoDB, formerly 10gen, is the main vendor behind the NoSQL database of the same name, which developed the database and open sourced it.

Most of the NoSQL vendors adhere to the open source-plus business model: they make a basic version of their version of the database available for free and monetize and enterprise version often with associated proprietary management software and maintenance support. Most also offer professional services. From a competitive perspective, some NoSQL vendors compete with one another while others are more complementary.

In terms of marketshare, MarkLogic, with its eponymous document database, leads the market with 25% share (See Figure 4). Amazon, with its cloud-based DynamoDB NoSQL database, follows close behind with 21% marketshare. MongoDB and DataStax take the third and fourth positions with 11% and 10% share respectively. Couchbase has 4% share, followed by Basho, Aerospike and Neo Technology, which each have 3% share. The remaining 18% of the market is divided up by various professional services firms, ISVs and VARs.

NoSQL Market Drivers

The NoSQL market in 2014 is being driven by the desire of enterprise developers to build and support real-time, interactive data-driven applications that incorporate not just structured data but all manner of semi-structured and unstructured data as well. These applications take many forms, but most involve delivering data and information to end-users in the form of interactive web and mobile applications.

NoSQL databases provide an ideal platform for these types of applications because they do not require developers to define the data schema or format in advance. Most NoSQL databases also run on commodity hardware, meaning they easily scale linearly by simply adding nodes to the cluster. Both these attributes are radically different than the approach taken by most proprietary, relational databases and give application developers significantly more flexibility as to the types and size of applications they can build and support.

In addition to end-user applications, a number of NoSQL early adopters are also using the technology to support applications that intelligently automate business processes. The adtech use case is likely the most familiar to most consumers, but these real-time, in-line analytic applications are increasingly finding their way into the financial services and industrial sectors. Many emerging applications designed to leverage sensor and machine-generated data created as part of the Internet of Things are also built on NoSQL foundations.

These types of applications enable enterprises to operationalize the insights and predictive models that are uncovered and built with the help of Hadoop and other analytic environments. The two, Hadoop and NoSQL, or Deep Data Analytics and In-Line Analytics, are two sides of the same coin.

In addition to the new applications NoSQL enables, and like Hadoop, NoSQL approaches are also significantly less costly than those offered by proprietary RDBMS offerings. This is due in part to the open source nature of most NoSQL database software as well as the inexpensive off-the-shelf hardware that most run on. As a result, a small but growing percentage of enterprise developers replacing the underlying RDBMS supporting existing applications with one or another NoSQL database.

NoSQL Market Headwinds

The NoSQL market faces a number of challenges to growth from a vendor revenue perspective.

The first, and again like Hadoop, is that most NoSQL database technology is relatively immature, especially when compared to relational database technology that has been around for over thirty years. While NoSQL database technology provides significantly more flexibility in terms of data type, most lack the same level of enterprise-grade security, data consistency, resiliency and backup capabilities as their relational database counterparts.

According to Wikibon’s 2014 Big Data adoption survey, over 25% of Big Data early adopters have deployed or are evaluating NoSQL database technology. The biggest barriers to successful NoSQL projects, according to these practitioners, are concerns about maintaining application performance as both data volumes and concurrent users increase; concerns about data backup and recovery; and data security and privacy concerns. Data consistency is also an area of concern for NoSQL practitioners and is particularly important for transactional applications.

Major NoSQL Market Developments

2014 was an eventful year for the NoSQL market. The various market participants continued to jostle for position, with several securing large funding rounds. The biggest recipient in 2014 was DataStax, who secured $106 million in Series E funding in September (See Figure 5). Earlier in the year, Couchbase raised $60 million, also in Series E funding. From a market consolidation standpoint, IBM acquired Cloudant, which competes with Couchbase in commercializing Apache Couchbase but specializes in cloud-based deployments of the NoSQL database.

The biggest news of the year was a change in leadership at one of the leading NoSQL vendors. Max Schireson stepped down in August as CEO of MongoDB. In a well-publicised blog post, Schireson cited his desire to spend more time with family as his reason for stepping aside from “the best job I ever had.” Venture capitalist and former BMC executive Dev Ittycheria was named to the top spot to replace Schireson.

While Wikibon takes Schireson at his word regarding his departure from MongoDB, the reality is that the company – as well as many of its NoSQL competitors – are struggling to develop and implement sustainable business models. Commercializing open source software is challenging, as we’ve seen in the Hadoop space, especially when its popularity is driven by an active and passionate community of committers and practitioners. This is certainly the case with MongoDB, which is extremely popular with developers. However, MongoDB has not capitalized that popularity into significant profits, as Schireson himself alluded to in his keynote address at MongoDB World in June, two months prior to his recognition.

In short, NoSQL vendors like MongoDB need to strike a balance between increasing price per unit and establishing a realistic path to profitability while simultaneously maintaining the support of the open source community, without which there would be no NoSQL market in the first place.

NoSQL Market in 2015 and Beyond

Over the long term, Wikibon believes the NoSQL market will enjoy significant growth, eventually outpacing the Hadoop market. This is due to the potential value that NoSQL databases can deliver via operationalizing Big Data insights. While Hadoop and related analytics technologies allow enterprise practitioners to discover important insights, NoSQL translates them into automated actions that, in many cases, directly impact the bottom-line.

In 2015, Wikibon forecasts the NoSQL market for software and support subscriptions as well as professional services to grow to $643 million from $411 million in 2014. That represents year-over-year growth of 56%. The NoSQL market will top $1.5 billion in 2017, leaving it just slightly smaller than the Hadoop market. Wikibon expects the NoSQL market size to exceed the Hadoop market by 2020.

Conclusion

The Hadoop and NoSQL markets are in the midst of significant growth and tremendous innovation. Enterprise practitioners are frustrated with existing approaches to both data warehousing and RDBMS and are actively looking for more cost-effective, scalable, flexible and agile approaches to data management. The ultimate driver of these markets, however, is not cost savings but the need on the part of all enterprises to make better use of their data assets to remain competitive in the fast moving business environment. Enterprise practitioners that have yet to do so should begin evaluating Big Data use cases and developing realistic plans to adopt Big Data technology to support executing against these use cases.